CRT is not History. CRT is Woke Historiography

Critical race theory has been much discussed over the last few years. Strangely, the meaning of the expression has evaded clear explanation. By and large, its detractors have claimed to be an ideological falsification of American history bound to reduce its heritage and identity to an innate and terminal racism, which is present even in the least suspecting. Its supporters claim CRT, as the American acronymic compulsion would have it, to be the articulation of historical truth which see American history, its heritage and American identity by and large to be reducible to an innate and terminal racism which is present even in the least suspecting.

The other red pill

The confusion about Critical Race Theory which accompanies almost every public debate on the issue in the American market of knockoff ideas is possibly a reflection of a collective lack of rudimentary knowledge concerning not only history but its practice and scope.

CRT is often presented by its accolytes as unmediated and uninterpreted factand by its detractors as lies. History is no longer interpretation, back to medieval historizicing: history is gospel and moral lesson.

This is not merely the type of historical illiteracy that one has come to expect from the American public. More alarmingly, this debate exposes a lack of intellectual literacy that comes from loosing sight of the suspension of disbelief that all forms of narrative demand of the reader. In perhaps words that even those I am attacking here can understand, the American public seems to have lost all sense that all that we know about history is the product of various interpretations and thus various biases and their mutual comparison. All of it. Even the one narrative wefavour. And it is indeed that one whose presumptions are the most important to keep in sight so as to avoid lapsing into dogma.

Spielbergian History

It might well be the case that in the American cultural context, this gullibility is exacerbated by the fact that history is often learned through film — in the age of Netflix the blurring of the line between documentation and fiction has become a new form of art — which reproducing the perceptive granularity of actual experience is much more capable of giving the dim of wit the impression that the reality of the depiction is the reality of what is depicted.

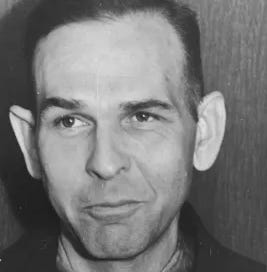

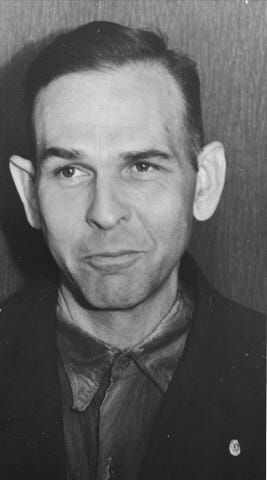

In some sense, this is the age of Schindler’s List. The blatant manipulation of American intellectual illiteracy by disguising fiction as fact. Spielberg’s Krakow managed to effectively hide beneath the false archival black and white of the movie the fact that the movie was fiction. With the hand of the director expertly concealed and the image aptly mimicking the grain of the celulloide from historical archives, the public was sold a counterfeit Amon Göth, dispensing with the large ears and bestowing upon him a perfectly shaped head in which masculine beauty could furnish a quasi-cosmic image of evil. Not only the audience could not tell appart from the original but which much better suited their moral intuitions and political aspirations. To praphrase a line somwhere in Wim Wenders’ State of Things “Life is in colour but black and white is much more realistic.”

In this sense, the curious aspect of the way that American socio-political ideary and its political foundations recruit fiction as history by quite simply disregarding the narrative context. After all, when the lights are out it is impossible to say if you are watching history in a museum or in a film multiplex.

The upshot is that instead of approaching history as a set of interpretative exercises liable to comparison, reevaluation, enmendation and correction, the American political ideary with its loud narrative approach history as contrapositions of truths and lies in which one’s favoured account is embued not merely with accuracy but with moral worth. As proof stands Spielberg’s (read Schindler’s) little girl in the red coat. How much more vivid can history be?

The Amazing Grace of the Red Pill

What for most adults ought to be adynamic economy of historical knowledge, in the US has become little more than competing gospels in various competing projects of political soteriologiy.

It is the American right that in its more reactionary forms has found a fit way to summarize this soteriological aspiration in famous and infamous red pill.

The red pill, inherited from the Wachosky former brothers’ adolescent philosophical machinations stemming from poorly-taken notes during philosophy classes, is indeed a mechanism of illumination. By taking the red pill, the main charater of the Matrix is capable of seeing beyond the limit of his normal vision things as they really are. What he took to be reality was an illusion seen, as it were, through a glass darkly. His account of history, his own and that of others, was deformed by a vision perverted by poor habits of conscience which, in the movie, reflect the evident moral shortcomings of the comforts afforded by economic safety. The pill, like all forms of mystical rapture, allows him to see not only beyond this illusiong but more importantly allows him to see this illusion from beyond. In this sense, the red pill is, as all mystical raptirures, an historiographical contraption.

Far from offering the critical awareness that many of the political peddlers of red pills seem to believe it does, the long term effects are, unsurprisingly, not well understood. The red pill, as a final reatrticulation of the present through the past, that is to say, through the final and true vision of history is the elaboration and endorsement of dogma. In the reactionary political context this dogma is ideologially built on the most trite of American devices for self-deception: virtuous individualism, moral heroism and, as foils of course, perverse communitarism and immoral pacifism, etc. Thus, the new talking points of the right according to whom Franco offered heroic resistance to republican communism and Hitler was a socialist— both new tropes of right-wing historical narratives— are no more and no less than ideological historiographies.

CRT pills and a glass of water

This pill, a piece of lowly popular culture redeployed as a pharmaco-political cliche, is perhaps one of the best way to understand CRT and its function. Much like the various pills that the right likes to pop, CRT is a soteriological project too. It does exactly what the pill does. If you drink it or smoke it, it will allows you to see history as it really was and it forever will have been. For good reason, Walter Benjamin called this form of naive historiography “the strongest narcotic of the 19th century.” Who could have predicted that this would be the strongest narcotic of the American 21st century too.

In a country devoted to dime-store metaphysics and pharmacological solutions, the red pill and the CRT pill are nothing else than mind-altering concoction, mechanism for epistemological salvation, the condition of access to historical truth. (That was a tricolon and you will survive.)

In this sense, the battle lines are not only well-defined but require very little consideration. It is about choosing truth against lies. On what side of that battle would one stands is not just an epistemological question but given that CRT is built upon the topology of unspeakable racial crimes, the demand to interpret history under its guise carries with it the implicit imputation of total moral turpitude to the apostates. In some sense, one is free not to take the CRT pill but that means freely choosing to be a racist, apologist of slavery, etc, etc.